By Natasha Ouslis and Zad El-Makkaoui

Companies invest in high potential programs with the goal of developing their star employees into future leaders. As exciting as these programs seem, poorly designed versions of them might cause more harm than good. While there is no secret recipe for a high potential program, here are three ideas to keep in mind when designing your company’s program to ensure it is effective and fair:

1. Companies that invest in high potential programs financially outperform their competitors.1

High potential programs sit in talent management, a practice that focuses on identifying and developing the ‘A players’— those who have the highest leadership potential and are of great interest to companies — with the potential to fill future leadership roles.2 This segmentation of the workforce allows companies to achieve their business objectives and motivates those labeled as high potential A players to strive and thrive. After tracking 300 organizations across 31 countries over 7 years, researchers found that investment in high potential programs correlated with better financial performance.1

These programs are not faultless, however. Regardless of intention, high potential programs can alienate the B players who make 80-85% of the workforce,3 leading to demotivation, a decrease in productivity and engagement,4 and even at times, higher turnover.5

2. The risk is worth the outcome if the high potential program is robust and grounded in science

Talent management experts need to design programs that clearly outline the variables that make a candidate ‘high potential’ if these programs are to succeed. Strong programs use evidence-based frameworks that can define, identify, and develop potential. Companies risk falling into the trap of misidentifying high potentials and losing future leaders if they identify the wrong candidates

3. The Leadership Potential Blueprint outlines key variables you can use to build an effective high potential program

The Leadership Potential Blueprint is a framework used by organizations to develop their own talent management strategies and make critical decisions about talent.2

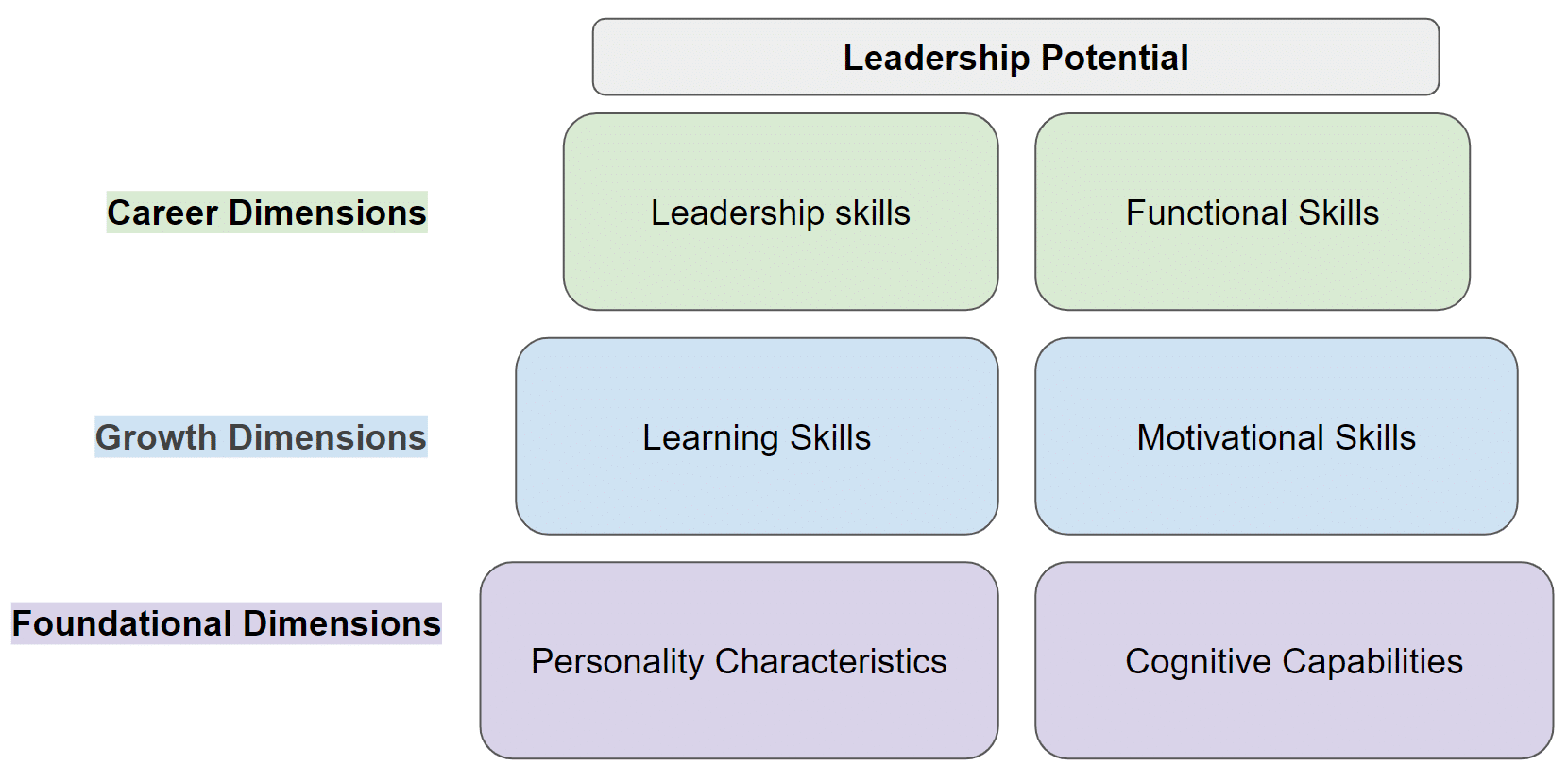

This framework focuses on a handful of variables that predict potential. These elements can identify (and develop) the ‘A players’. The framework consists of three dimensions, each containing two variables, organized from the most stable to the most changeable skills and abilities.

A) Foundational dimension: Personality & Cognition

The foundational dimensions consist of the two variables that are unlikely to change — personality characteristics and cognitive capabilities.

Personality characteristics are important to consider. They can shed light on a key aspect of leadership: How does this person interact with and influence others? Some of these characteristics are social and interpersonal skills, assertiveness, dominance, maturity, emotional self-control, and resilience.

Cognitive capabilities predict performance6 and, given their stability, can be great metrics for identifying high potential employees. Leaders who address the daily challenges of running a business need strong cognitive capabilities. These include intelligence, strategic, conceptual thinking, and the ability to deal with ambiguity and complexity.

B) Growth dimension: Learning & Motivation

The growth dimension consists of learning and motivation. These skills are the less stable, more developable elements that reflect an individual’s willingness to learn from new experiences.

In an ever-changing world where businesses and markets are in continuous flux, it is crucial for leaders to have (and use) key learning skills. As you identify high potential candidates, stay on the lookout for candidates who are adaptable, open to feedback, agile, growth-oriented, and eager to learn. Once identified, work on developing them further. Ensure your high potential program offers experiences, assignments, and training that challenge your candidates and nurture these skills.

Leaders are expected to motivate their constituents, so naturally, they themselves need to be motivated. Candidates who have motivational skills can achieve personal and organizational success. In the search for your A players, keep a lookout for whether or not candidates have drive, energy, ambition, a willingness to take risks, and a desire for achievement.

C) Career dimension: Leadership & Functional Skills

Finally, the career dimension comprises the variables that are the easiest to influence and develop — leadership skills and functional skills.

Leadership skills refer to an individual’s ability to manage, motivate, inspire, and develop others. As the name shows, leadership skills are critical for being an effective leader. While some candidates might have stronger dispositions for these leadership skills than others, they are developable. Therefore, high potential programs can foster leadership qualities amongst future leaders, especially if candidates get a head start.

Functional or technical skills refer to an individual’s possession of specialized and generalized business expertise and knowledge. Like leadership skills, they can be taught. The specifics of these skills vary across companies, teams, and roles — when you identify and develop high potentials using this variable, it is important to ask: ‘the potential for what?’

The future of high potential programs

Despite the risks, it seems that high potential programs are here to stay. As companies start to design (or redesign) their programs, they should use evidence-based frameworks to ensure they’re assessing and building talent in ways that align with their strategic objectives. For example, PepsiCo, Eli Lilly, and Citibank use the Leadership Potential Blueprint as the underlying framework for their talent management practices. If your company is looking to spruce its high potential programs up with more rigor and robustness, the Leadership Potential Blueprint is a great framework for identifying and developing your future leaders.

References

1. Bush, J., Skiba, T., Liu, W., & Li, A. (2016). The Financial Impact of Strategic Development and High Potential Programs. Journal of Organizational Psychology, 16(2). Retrieved from https://articlegateway.com/index.php/JOP/article/view/1794.

2. Silzer, R., & Church, A. H. (2009). The pearls and perils of identifying potential. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 2(4), 377-412.

3. Malik, A. R., & Singh, P. (2014). ‘High potential’ programs: Let’s hear it for ‘B’ players. Human Resource Management Review, 24 (4), 330-346. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2014.06.00

4. Saks, A.M. & Gruman, J.A. (2014). What do we really know about employee engagement? Human Resource Development Quarterly. 25 (2), 155-182.

5. Plessis, L. D. (2010). The Relationship between Perceived Talent Management Practices, Perceived Organizational Support (POS), Perceived Supervisor Support (PSS) and Intention to Quit amongst Generation Y Employees in the Recruitment Sector, University Of Pretoria.

6. Schmidt, F. L, & Hunter, J. (1998). The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 262-274.

This article originally appeared on thedecisionlab.com.